Articles

- Page Path

- HOME > J Powder Mater > Volume 32(5); 2025 > Article

-

Research Article

- Preparation of Flake-shape Cobalt Powders by High-Energy Ball Milling for rSOC Current Collectors

-

Poong-Yeon Kim1,2

, Min-Jeong Lee1

, Min-Jeong Lee1 , Hyeon Ju Kim1

, Hyeon Ju Kim1 , Su-Jin Yun1

, Su-Jin Yun1 , Si Young Chang3

, Si Young Chang3 , Jung-Yeul Yun1,*

, Jung-Yeul Yun1,*

-

Journal of Powder Materials 2025;32(5):383-389.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.4150/jpm.2025.00241

Published online: October 31, 2025

1Nanomaterials Research Center, Korea Institute of Materials Science KIMS, Changwon 51508, Republic of Korea

2Department of Materials Science and Engineering, Ulsan National Institute of Science and Technology, Ulsan 44919, Republic of Korea

3Department of Materials Science and Engineering, Korea Aerospace University, Goyang 10540, Republic of Korea

- *Corresponding author: Dr. J.-Y. Yun E-mail: yjy1706@kims.re.kr

© The Korean Powder Metallurgy & Materials Institute

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/) which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

- 445 Views

- 24 Download

Abstract

-

- Reversible solid oxide cells (rSOCs), which enable two-way conversion between electricity and hydrogen, have gained attention with the rise of hydrogen energy. However, foam-type current collectors in rSOC stacks exhibit poor structural controllability and limited electrode contact area. To address these limitations, this study aimed to convert spherical cobalt powders into flake-type morphology via high-energy ball milling, as a preliminary step toward fabricating flake-based current collectors.

- Milling parameters—specifically, the ball-to-powder ratio (BPR), milling time, and process control agent (PCA) content—were varied. At an 8:1 BPR, over 90% of the powder became flake-shaped after 8 hours, while extended milling caused cold welding. In contrast, a 10:1 BPR resulted in dominant fragmentation. The Burgio–Rojac model quantified energy input and defined the optimal range for flake formation. Increasing the PCA to 4 wt% delayed flake formation to 16 hours and induced cold welding, as shown by bimodal particle size distributions. These results support the development of Co-based current collectors for use in rSOCs.

- This study proposes an energy-optimized milling approach to transform spherical cobalt powders into flake morphology. Using controlled milling parameters, over 90% flake formation was achieved. These results support the development of Co-based current collectors for rSOC applications.

Graphical abstract

- With the increasing global demand for eco-friendly energy transitions, hydrogen-based clean energy technologies have attracted significant attention. Hydrogen has high energy density and generates only water as a byproduct during utilization. Moreover, it is highly versatile in terms of storage and transportation, making it an emerging energy carrier for future applications.

- Among the various hydrogen production methods, water electrolysis remains the most common and can be categorized into several types including polymer electrolyte membrane electrolysis cell (PEMEC), alkaline electrolysis cell (AEC), anion exchange membrane electrolysis cell (AEMEC), and solid oxide electrolysis cell (SOEC). SOECs are particularly advantageous due to their high efficiency and the absence of liquid electrolyte leakage, as they operate at high temperatures [1]. The hydrogen produced from such electrolysis processes can be reconverted into electricity through fuel cell systems. Major types of fuel cells include polymer electrolyte membrane fuel cell (PEMFC), alkaline fuel cell (AFC), phosphoric acid fuel cell (PAFC), molten carbonate fuel cell (MCFC), and solid oxide fuel cell (SOFC). SOFC, like SOEC, operates at high temperatures and offers high efficiency with the additional benefit of utilizing a wide range of fuels including hydrogen, natural gas, and methane [2-4].

- Reversible solid oxide cell (rSOC), which integrates the functionalities of both SOEC and SOFC, has emerged as a next-generation energy device capable of reversible energy conversion—enabling both hydrogen production through electrolysis and electricity generation via fuel cells [5]. A typical rSOC stack comprises an electrolyte, fuel electrode, air electrode, and a current collector. Among these, the current collector plays a crucial role by enabling gas diffusion, ensuring electrical contact with electrodes, and providing mechanical support. To fulfill these roles, the current collector must exhibit a highly porous architecture, thermal stability, electrical conductivity, and sufficient mechanical strength under operating conditions [6]. While metallic foams are commonly used as current collectors, their limited structural controllability and low interfacial contact with the electrode result in reduced electrical conductivity [7].

- To address these limitations, this study aims to replace conventional metal foam-type current collectors with a flake-type powder-based design, which is known to provide a larger interfacial contact area, lower contact resistance, and improved electrical conductivity [8]. To achieve this, cobalt (Co) powder—a transition metal commonly used in Co-based current collectors known for their excellent mechanical strength and electrical conductivity under high-temperature operation—was employed [9, 10]. The effects of milling parameters such as ball-to-powder ratio (BPR), milling time, and the addition of a process control agent (PCA) were investigated in terms of powder morphology and particle size distribution. Furthermore, the optimal conditions for converting spherical powders into flake-like morphologies were proposed.

1. Introduction

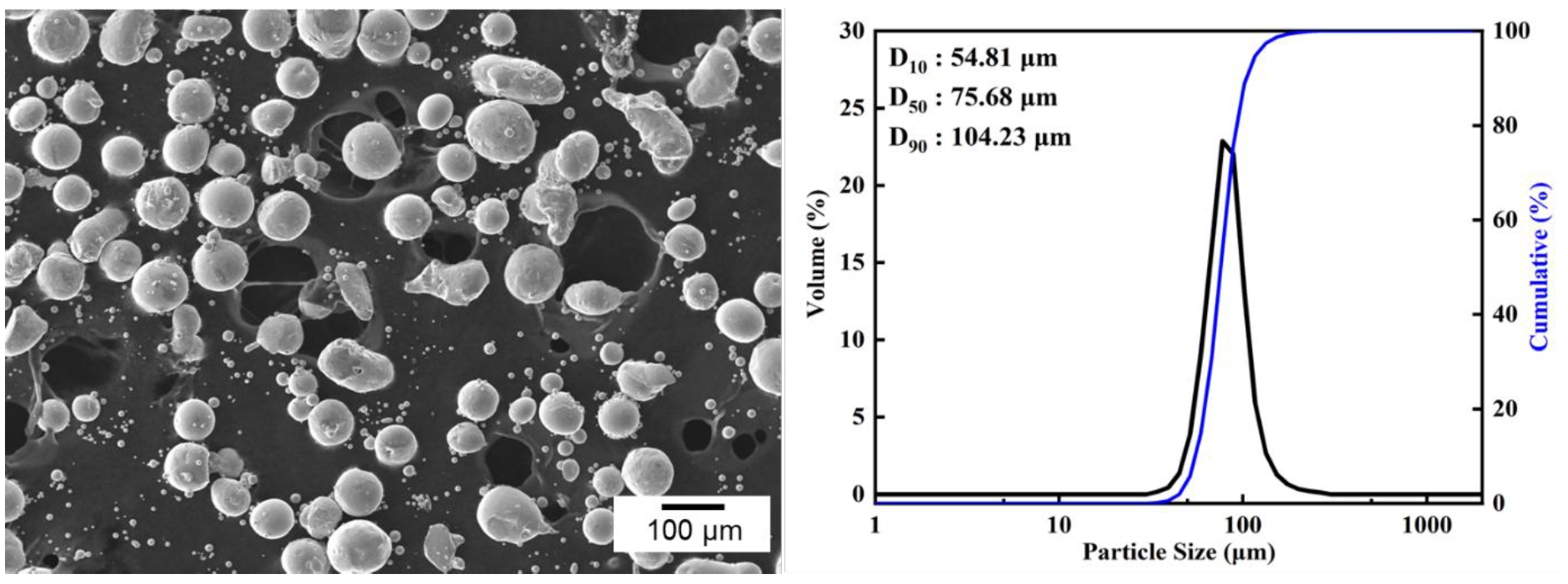

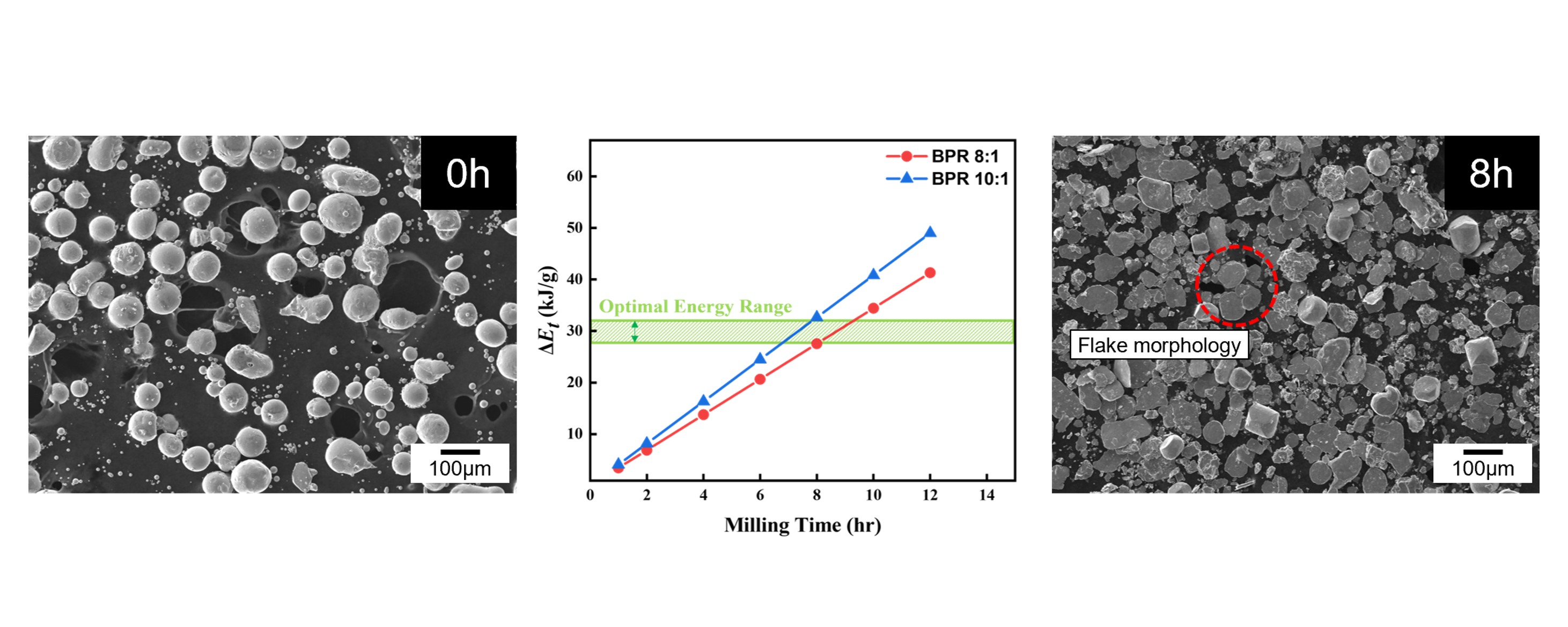

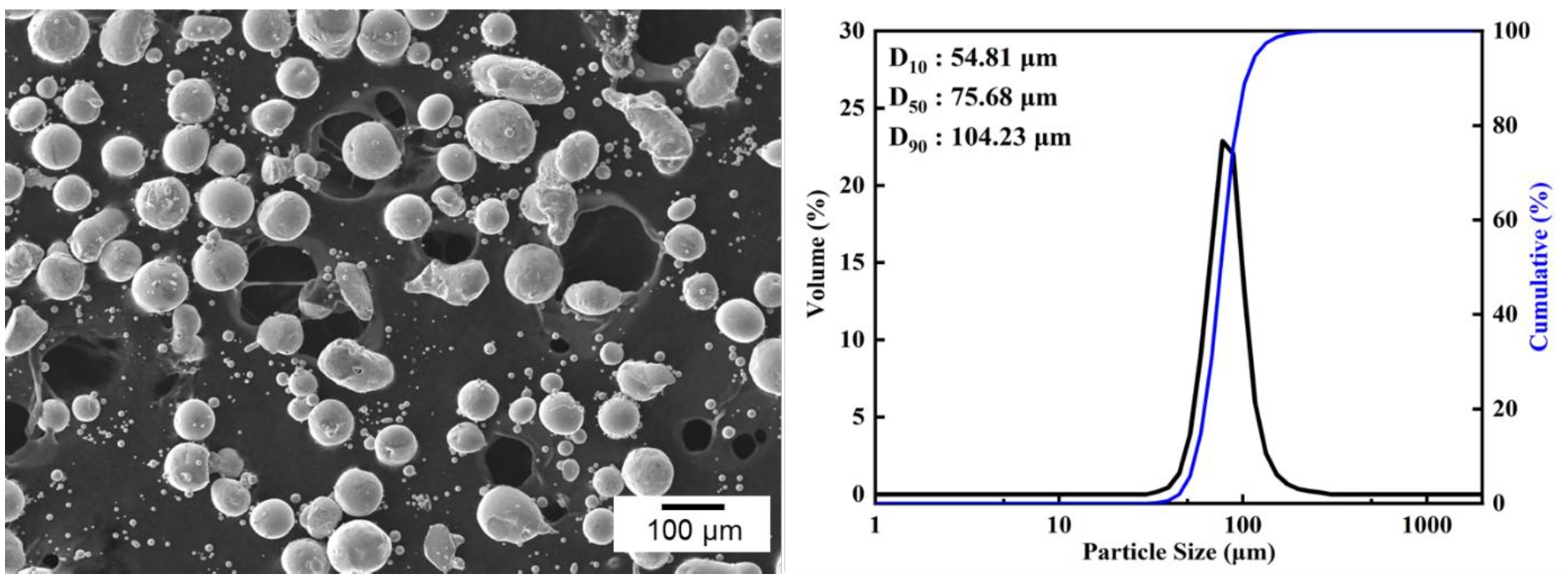

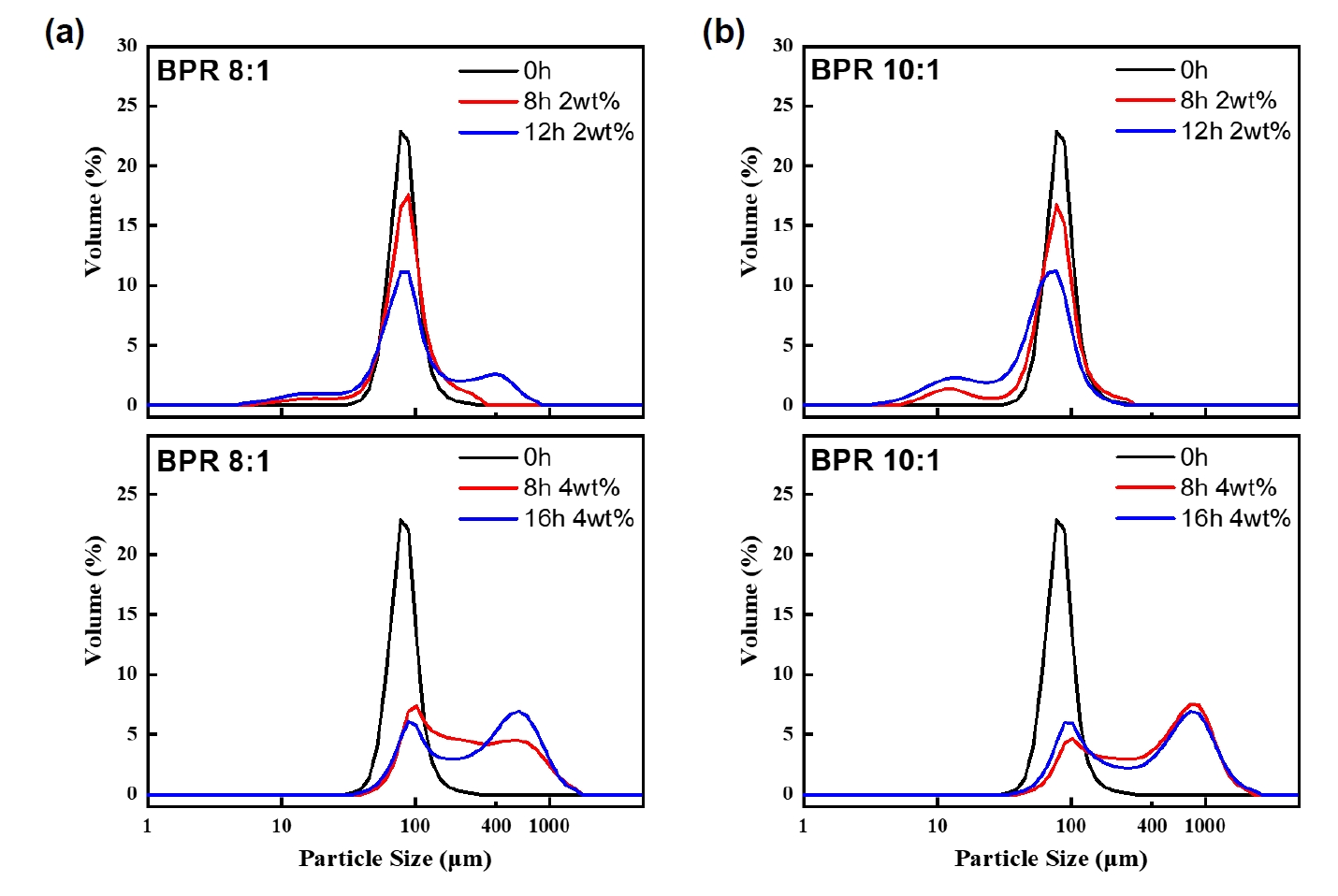

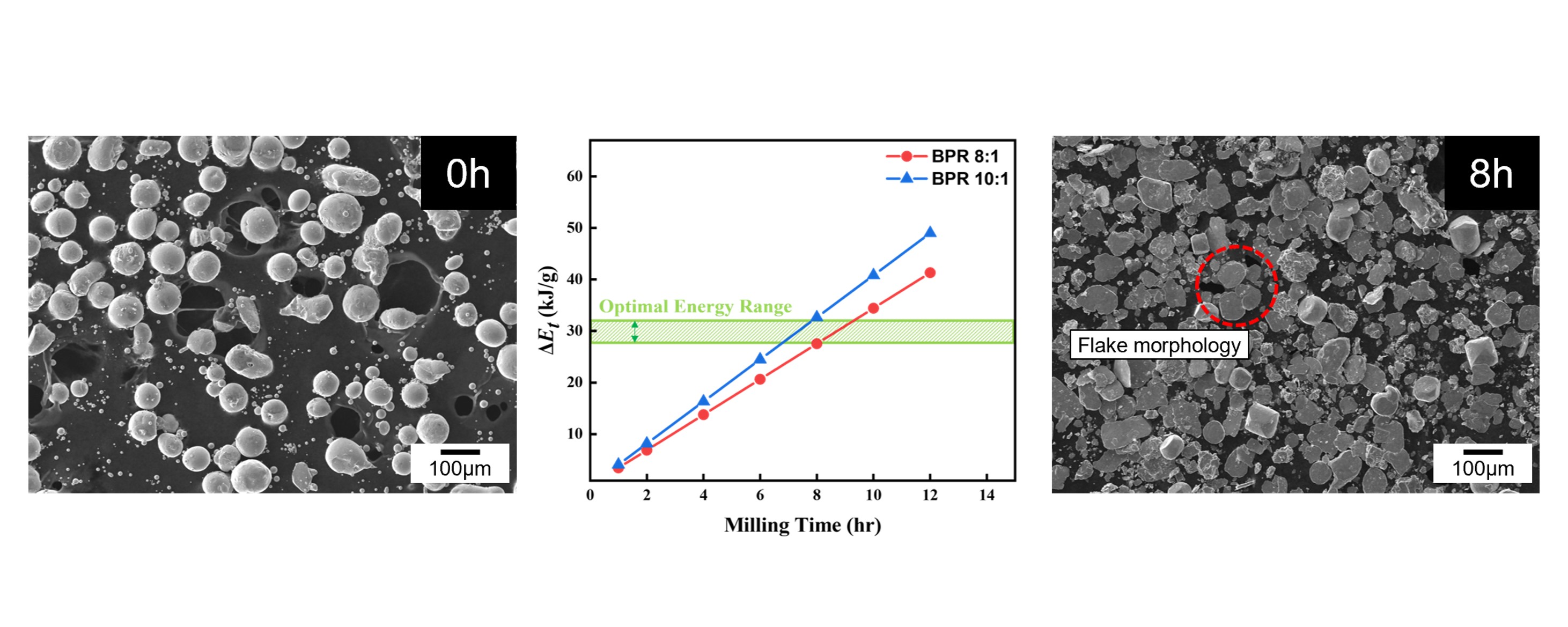

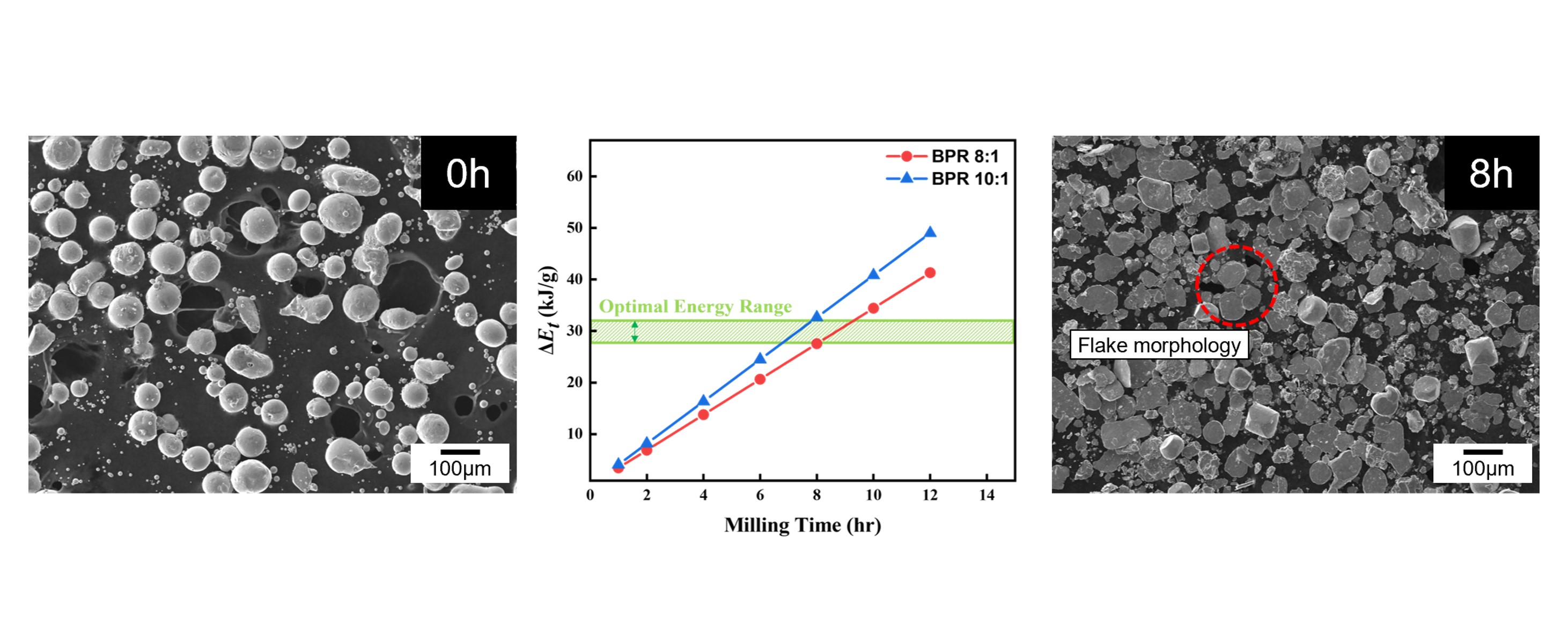

- In this study, a planetary ball mill (Pulverisette 6, FRITSCH, Germany) was employed to induce a morphological transformation of spherical Co powders into flake-like shapes. The starting powder used was 99.8% pure cobalt (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA), and its morphology and particle size distribution are shown in Fig. 1. The initial powder exhibited a spherical morphology with a D50 value of 75.68 μm. Both the milling vial and balls were made of zirconia, with ball diameters of 5 mm and a vial volume of 500 ml.

- Mechanical milling was carried out under two BPR conditions: 8:1 and 10:1. To prevent excessive heat during the process, milling was conducted in cycles of 10 minutes of milling and a 1 minute rest period. The powder mass and rotational speed were fixed at 40 g and 400 rpm, respectively.

- Stearic acid was used as PCA, and it was fully dissolved in ethanol at 55°C with stirring for 10 minutes before being mixed with the powder. The experiments were conducted with two PCA contents, 2 wt% and 4 wt%, and the milling time was varied from 4 to 16 hours at 2 hour intervals.

- After milling, the powders were dried at 70°C for approximately 1 hour to remove residual ethanol. Subsequently, thermal treatment was performed at 360°C for 1 hour under an argon atmosphere to eliminate the remaining stearic acid. The morphology and microstructure of the powders were observed using scanning electron microscopy (SEM, JSM-6610LV, JEOL), and particle size distribution was analyzed using a laser particle size analyzer (Partica LA-960V2, HORIBA).

2. Experimental Section

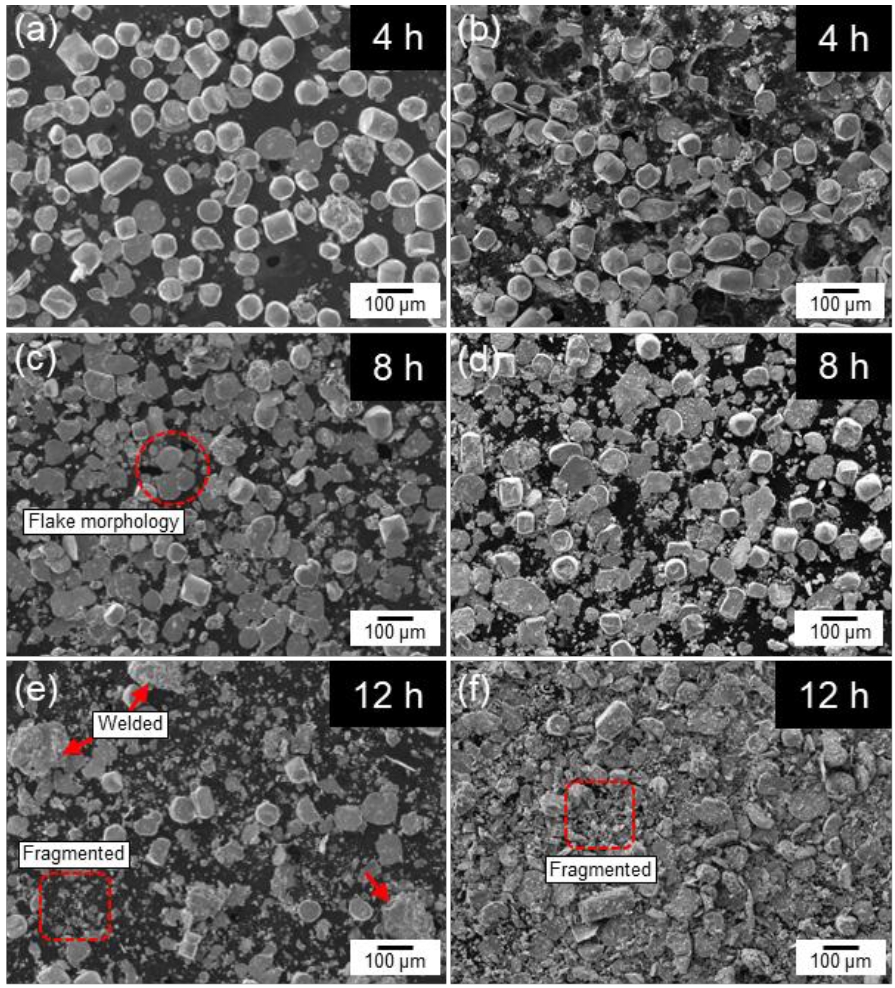

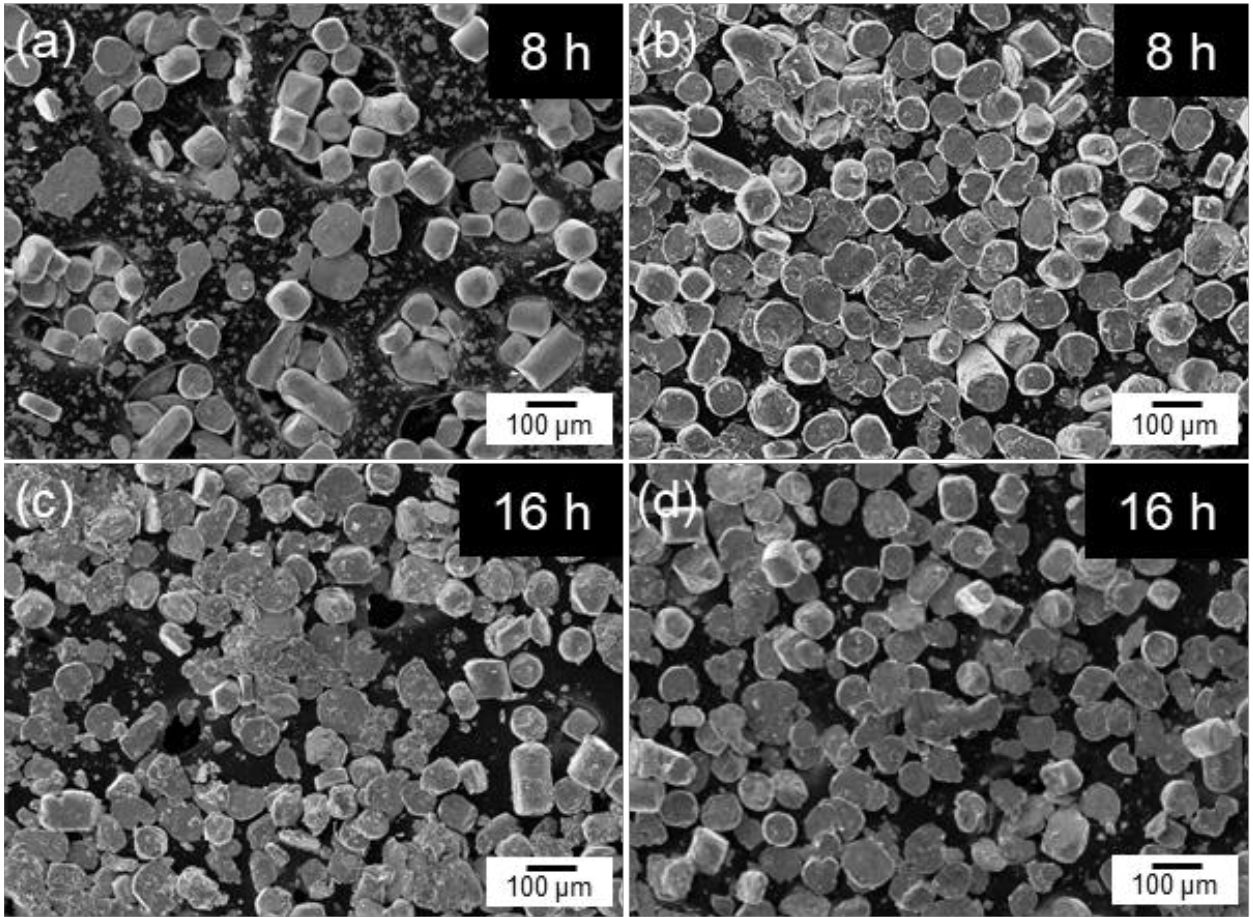

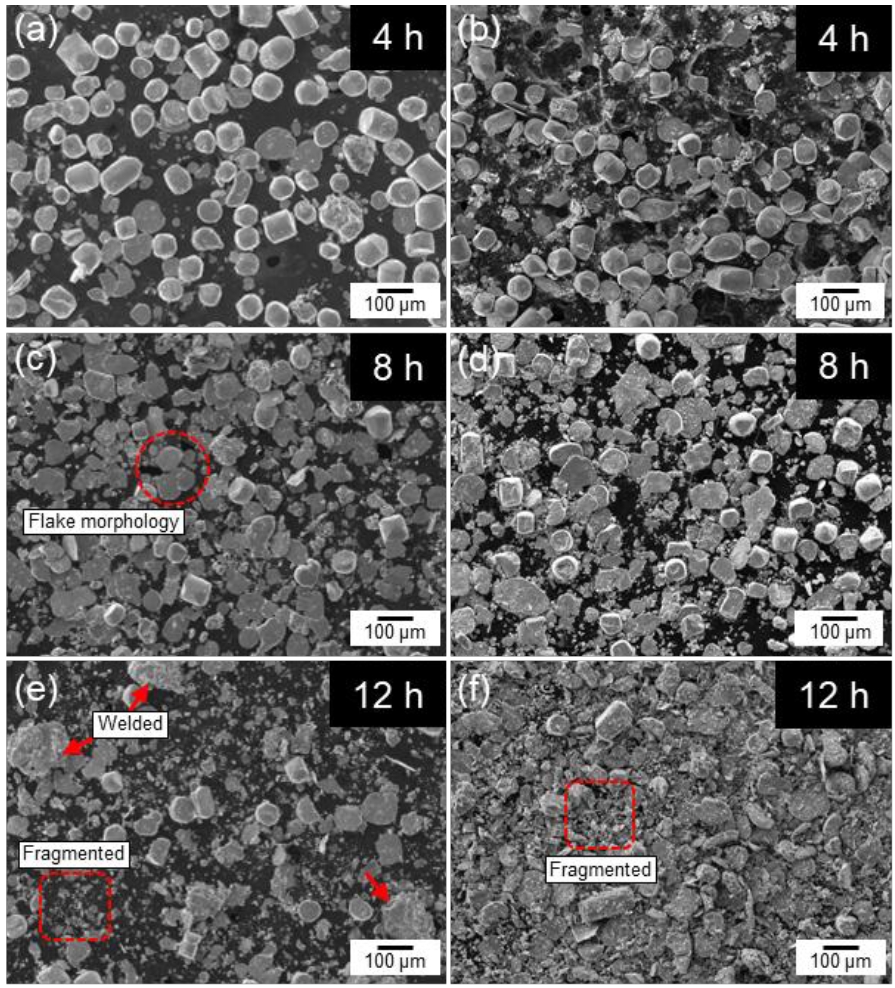

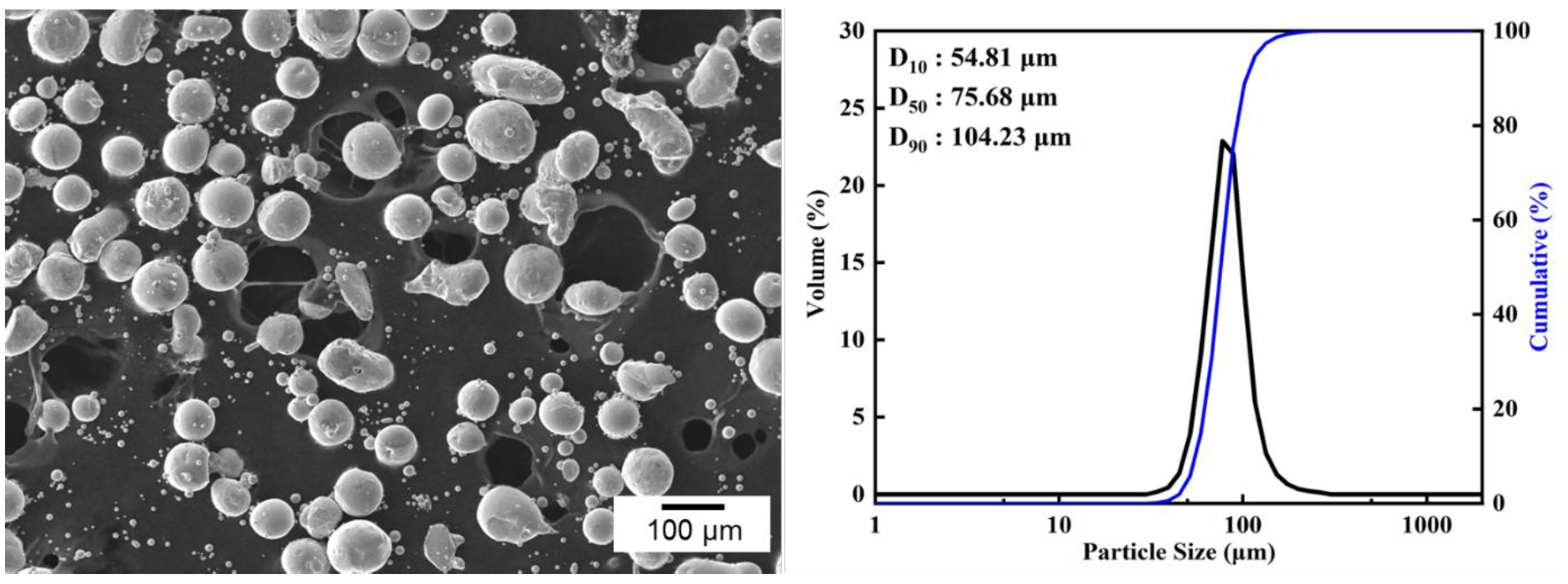

- Fig. 2 shows the SEM images of cobalt powders milled for 4, 8, and 12 hours under BPR 8:1 (a, c, e) and BPR 10:1 (b, d, f) conditions. In both conditions, some spherical powders were observed to be transformed into flake shapes even after 4 hours of milling. After 8 hours of milling, more than 90% of the powders under the BPR 8:1 condition were observed to have transformed into flake-shaped, while under the BPR 10:1 condition, not only flake formation but also fragmentation of some powders was observed. After 12 hours of milling, coarse particles were formed under the BPR 8:1 condition due to cold welding, and fragmentation also began to occur. In contrast, under the BPR 10:1 condition, fragmentation became more severe and many fine particles were observed.

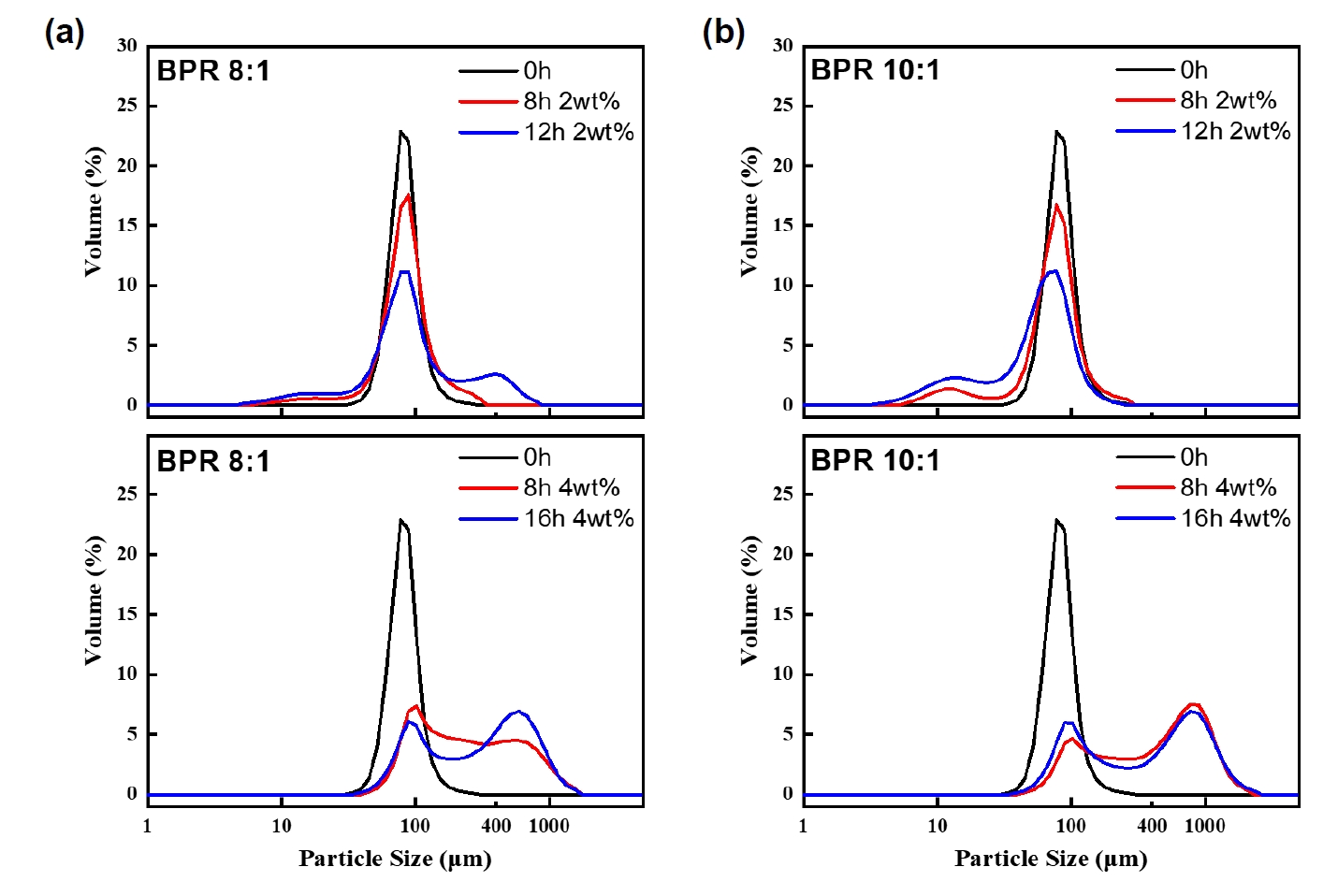

- As a reference for particle size analysis, the flake-shaped particles were assumed to be thin circular plates, and the volume-based equivalent spherical diameter was calculated based on the measured diameter and thickness [11]. When applying a diameter of approximately 80 μm and an observed thickness of 2 μm, the equivalent spherical diameter was calculated to be about 27 μm, whereas the original powder exhibited a D50 of 75.68 μm. This suggests, if the powders with a size corresponding to D50 are transformed into flakes, it would be expected that their particle size increases accordingly. However, the results obtained through equivalent spherical diameter analysis do not support this expectation. This implies that during the flake formation process, the original spherical volume is not entirely preserved. Instead, fragmentation and flake formation occur simultaneously, which reflects the brittleness of cobalt powders. This interpretation is also supported by the data shown in Fig. 3.

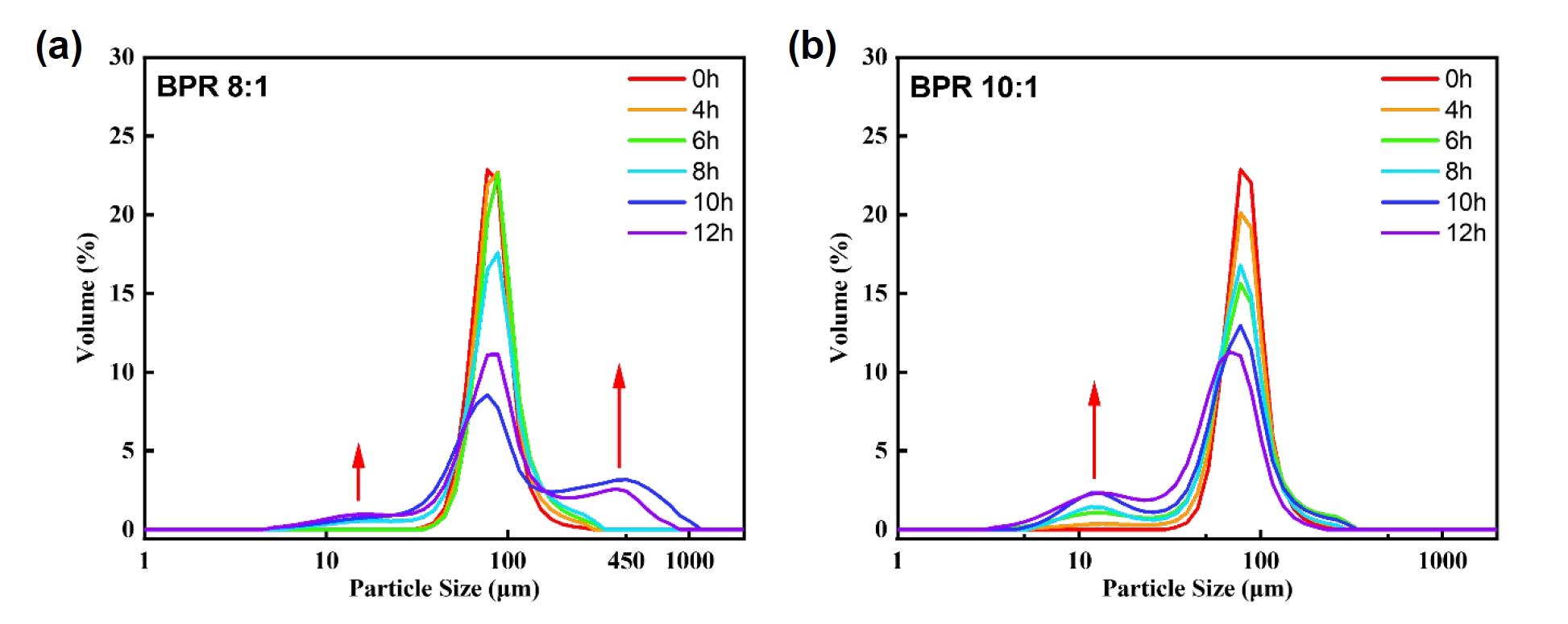

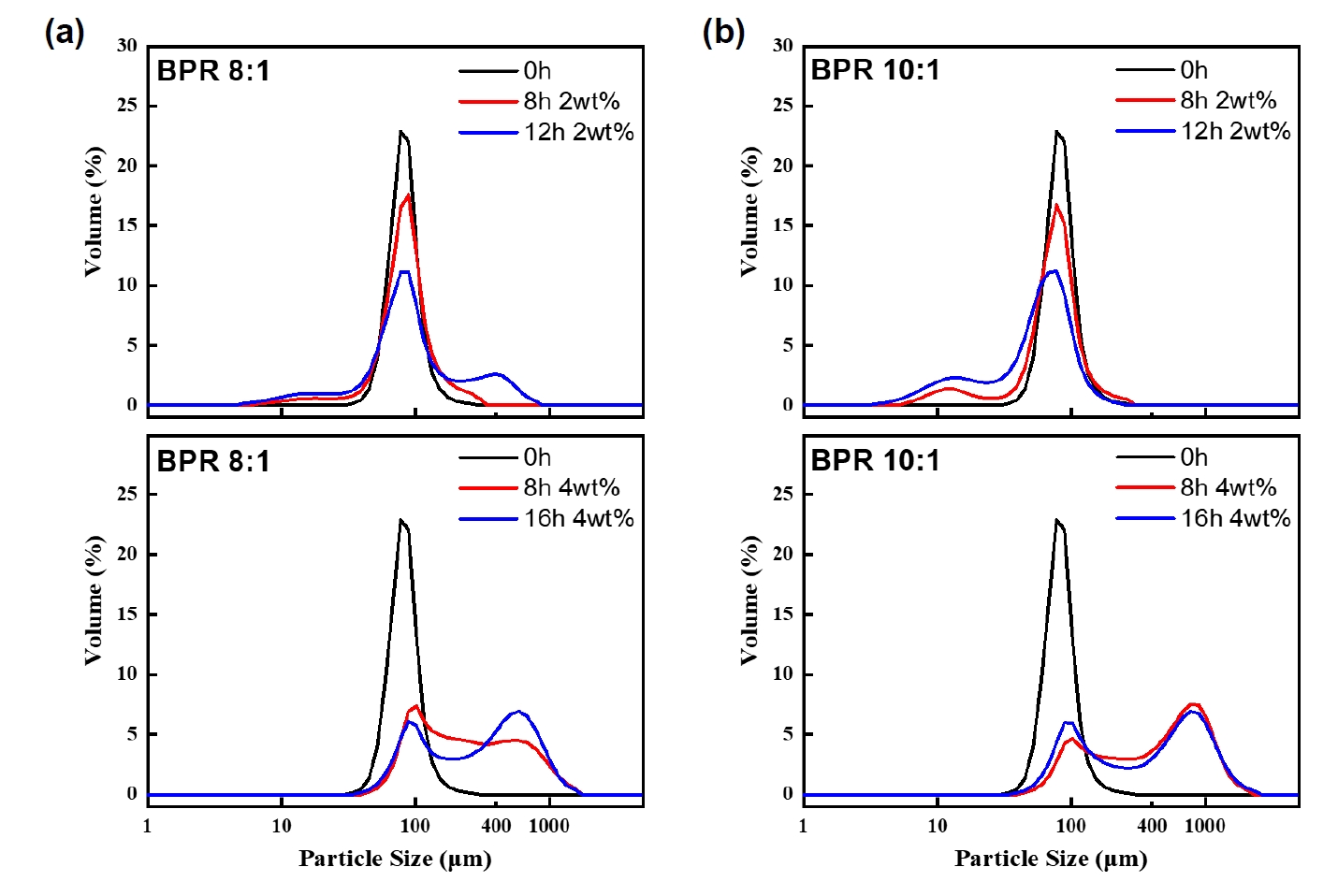

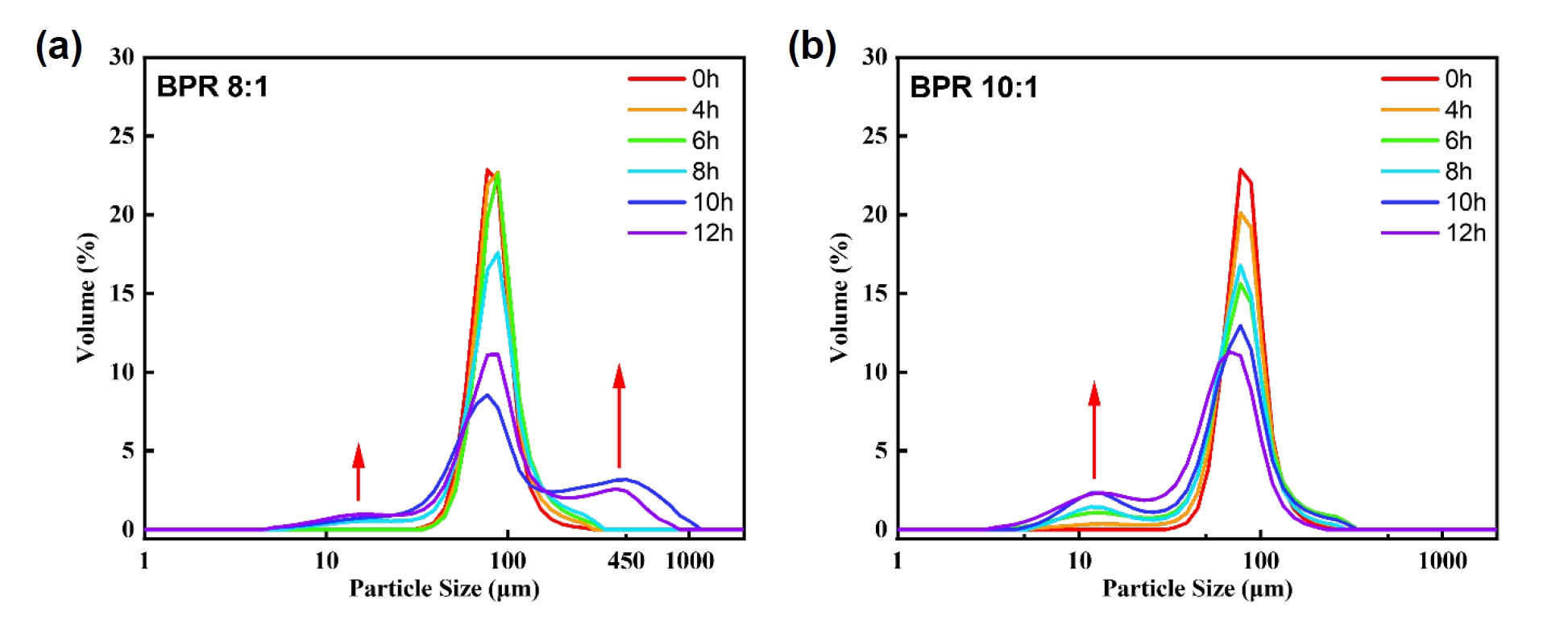

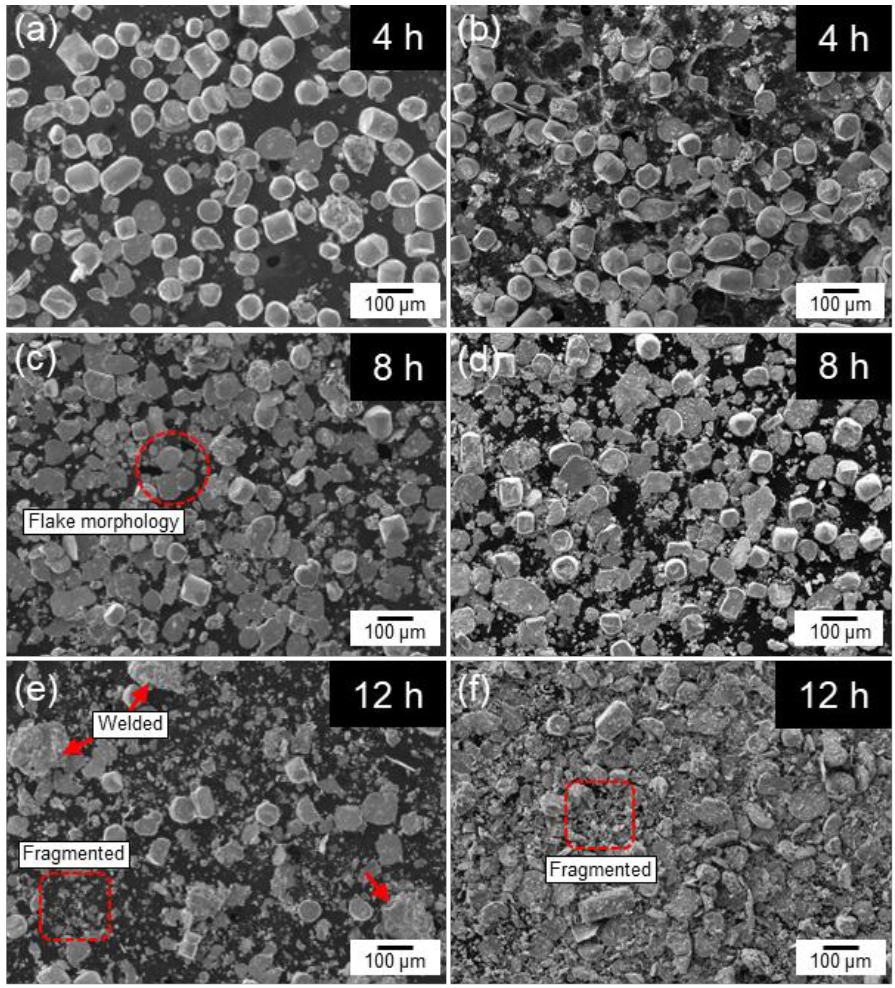

- Fig. 3 shows the particle size distribution results of the powders obtained under each condition. Under both BPR 8:1 and 10:1 conditions, the modal volume fraction decreased with increasing milling time. This indicates a redistribution of particle sizes, which was particularly noticeable after 8 hours in both conditions. In the case of BPR 8:1, as previously mentioned, flake formation and fragmentation occurred simultaneously, followed by cold welding, which became relatively dominant. Whereas in the case of BPR 10:1, fragmentation was clearly dominant over cold welding. This is interpreted to be due to the increase in collision frequency between powder and balls under high BPR, which increases the energy transferred to the powder and thereby promotes fragmentation.

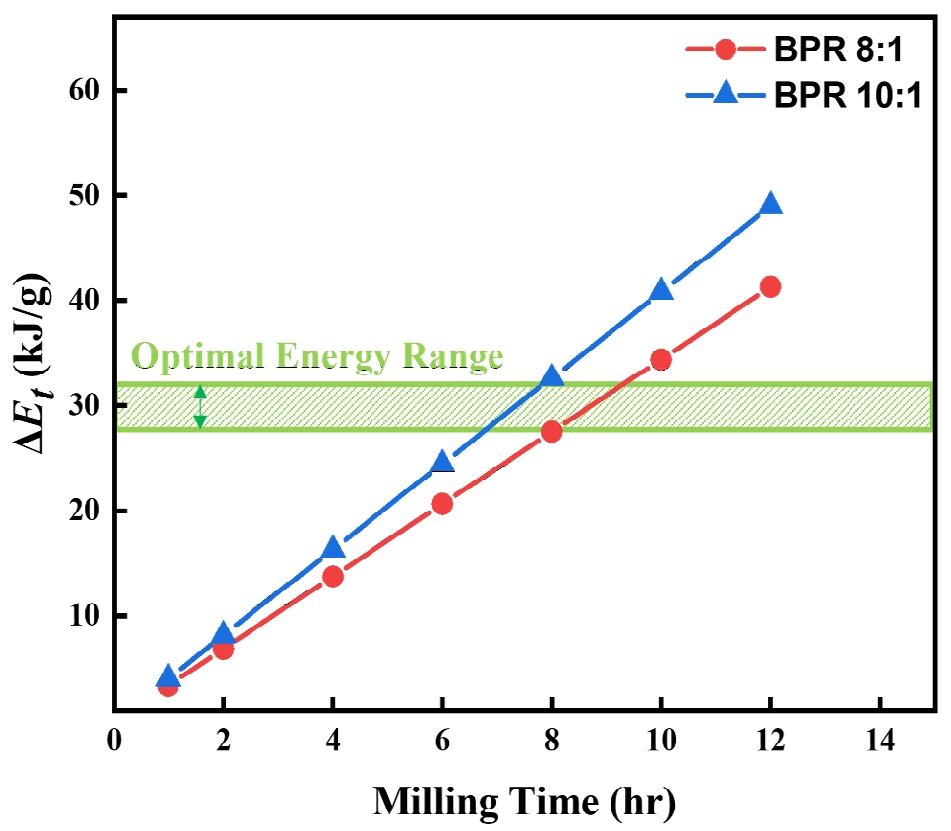

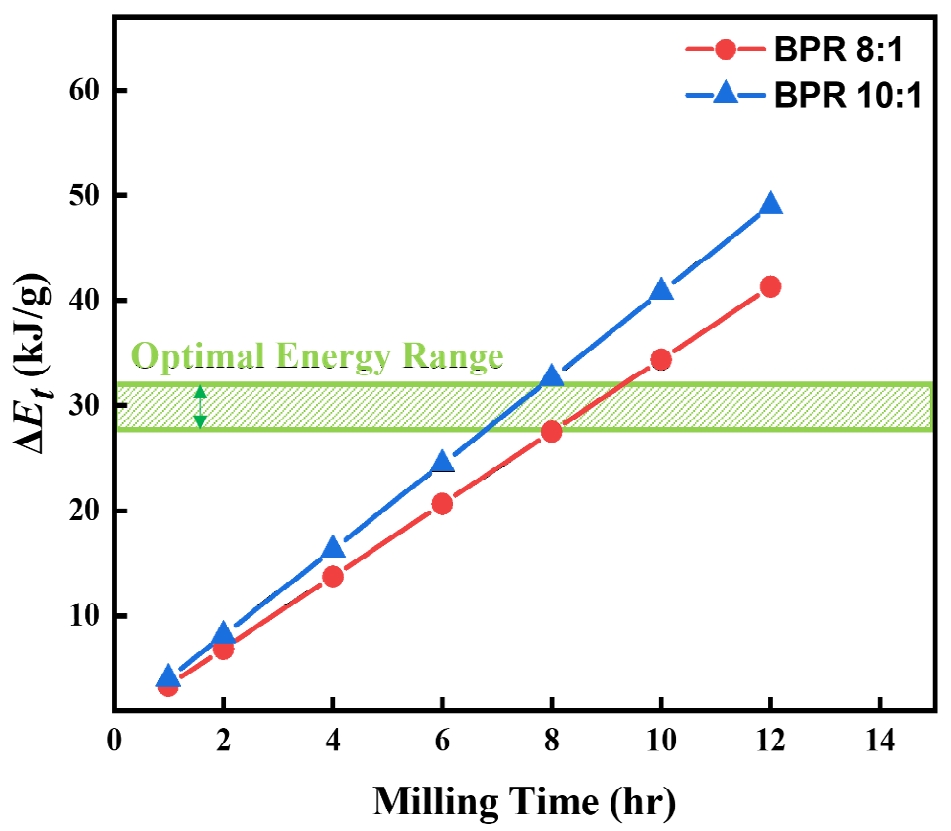

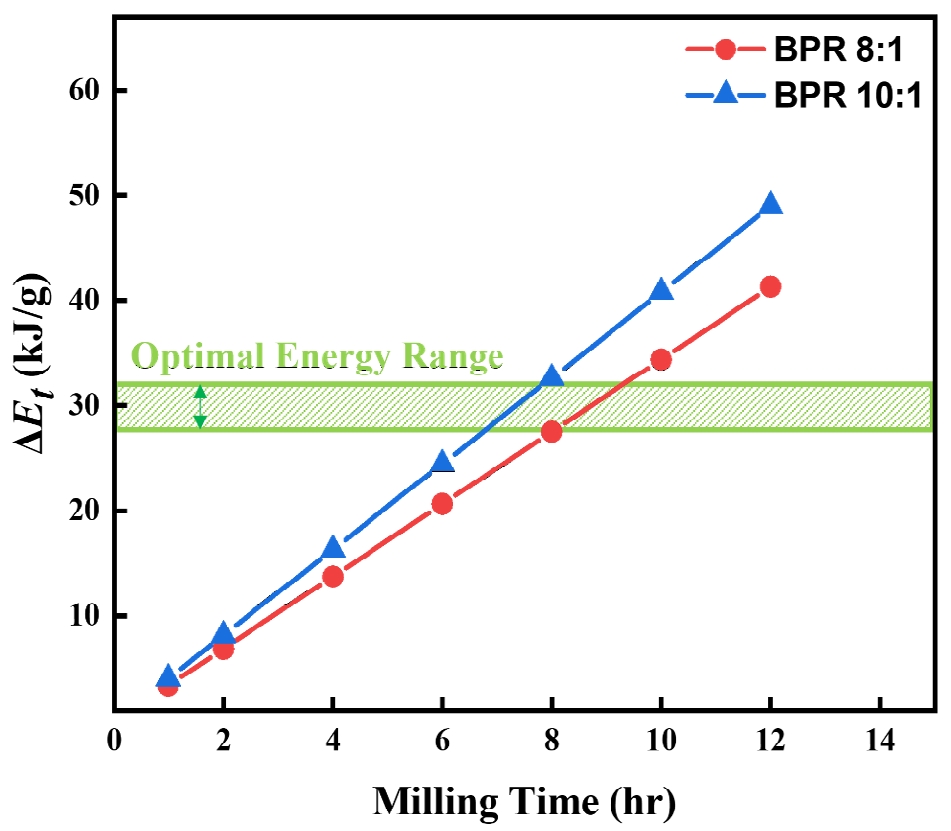

- The Burgio-Rojac model was employed to calculate the energy transferred to the powders, and the difference in energy input between BPR 8:1 and 10:1 was analyzed [12, 13].

- The parameter φb refers to the yield coefficient, which accounts for the interference between multiple balls. ∆Eb is the energy transferred to the powder per collision of a single ball, Nb is the total number of balls used, fb is the collision frequency, t is the milling time, and mpowder represents the mass of the powder.

- As shown in Fig. 4, the cumulative energy difference between the two BPR conditions tends to widen with increasing milling time. This difference is considered a key factor that determines whether fragmentation or cold welding becomes the dominant phenomenon in the powder. Accordingly, since over 90% flake formation was achieved after 8 hours of milling under the BPR 8:1 condition, and coarse particles appeared due to cold welding with further milling, whereas fragmentation occurred under the same duration at BPR 10:1, it is proposed that the energy range between these two conditions represents the optimal energy for transforming spherical cobalt powders into flake form. The excessive fragmentation observed at 12 h under BPR 10:1 (Fig. 2f), for instance, suggests the upper bound of this energy leads to particle breakage, whereas the lower bound of this energy (Fig. 2a and b) results in insufficient flake formation.

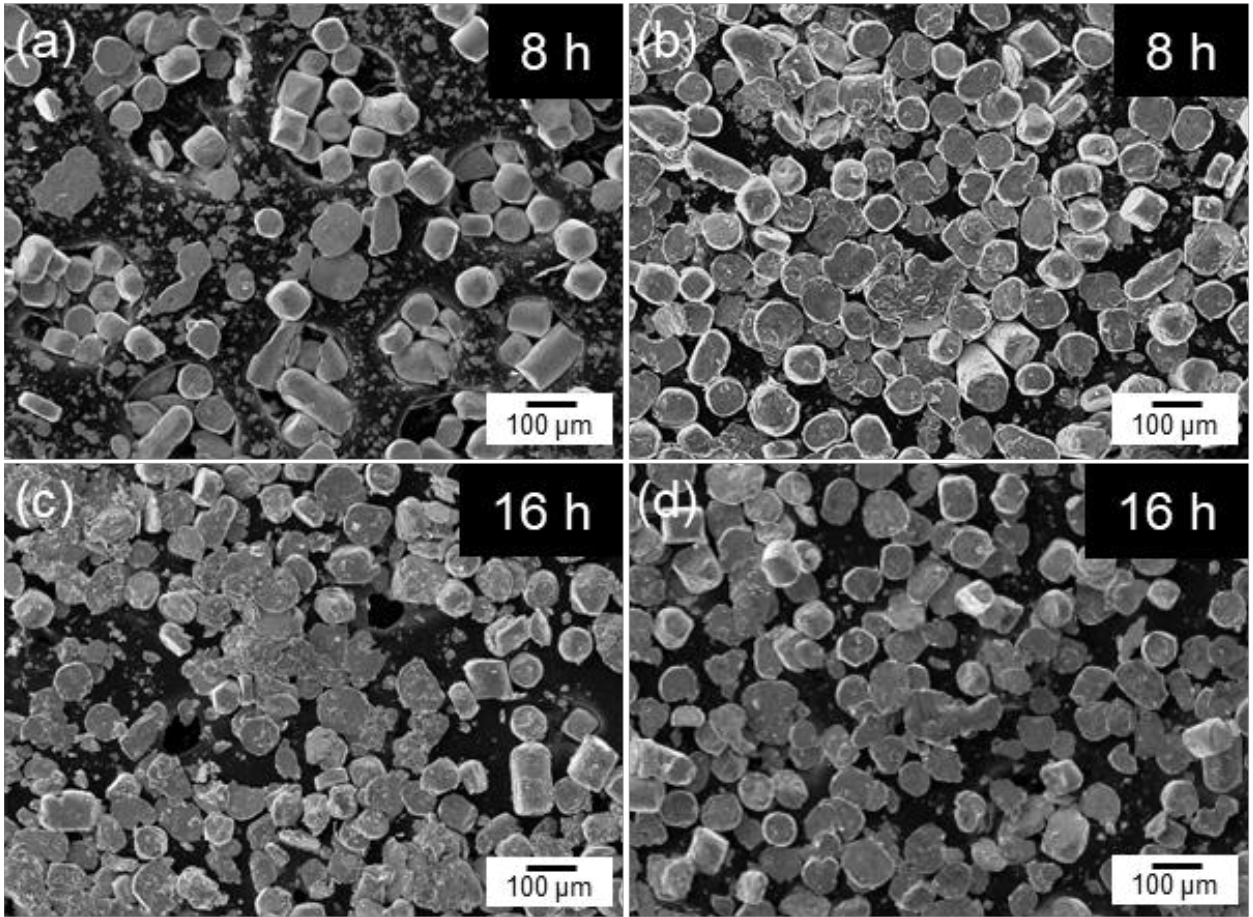

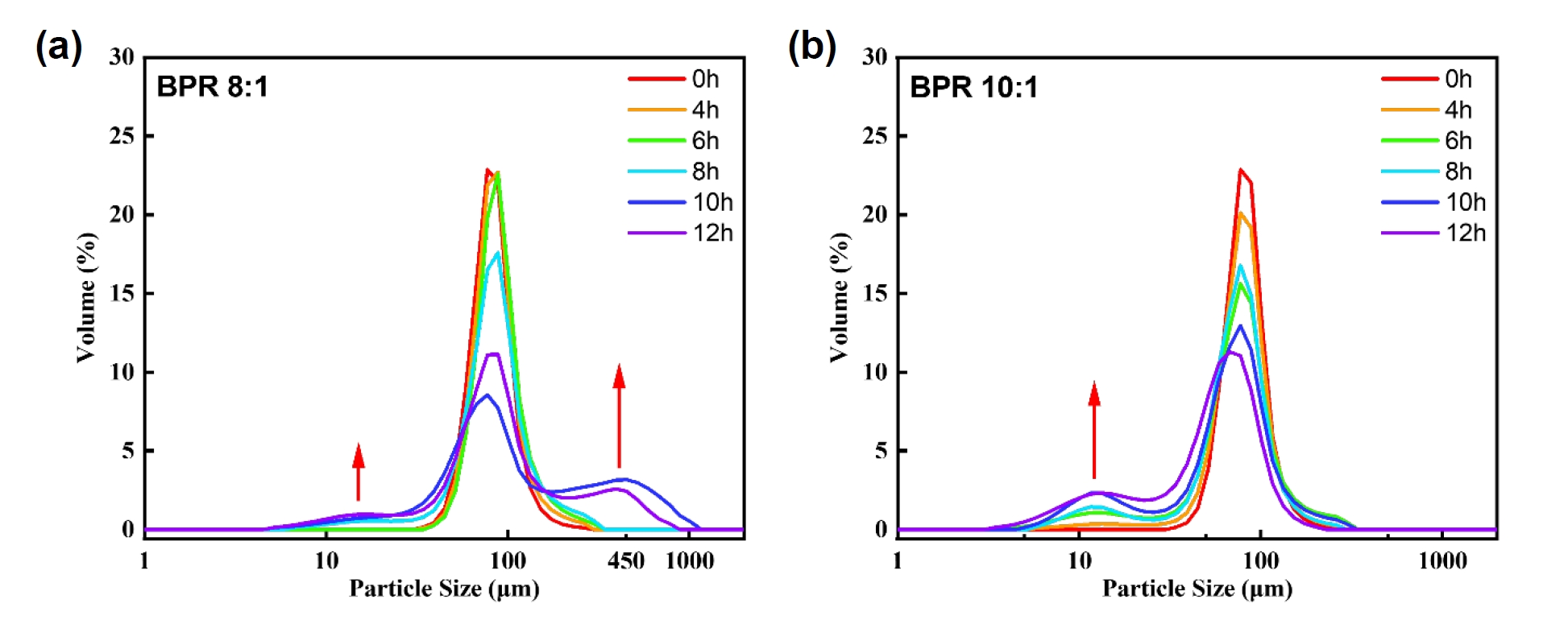

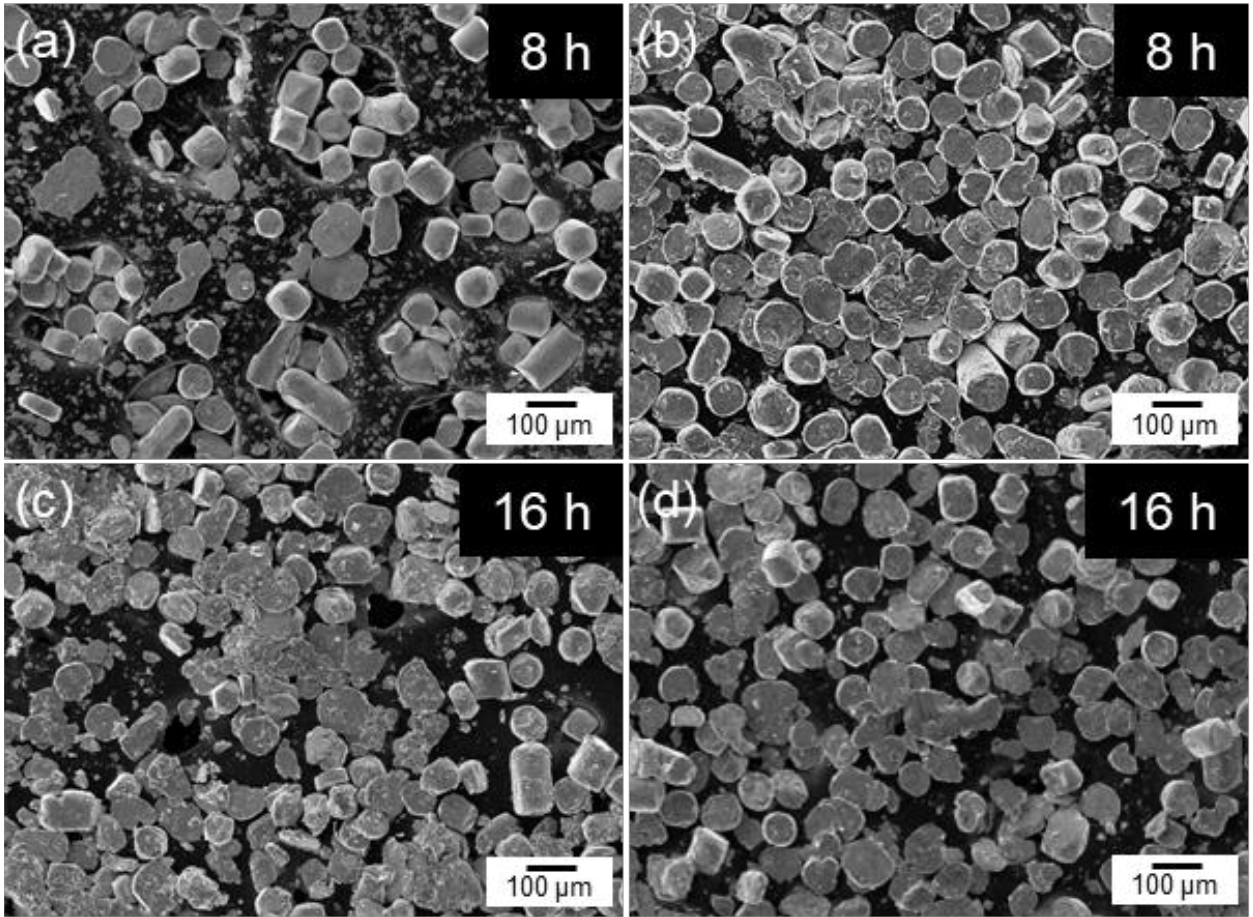

- As cold welding was observed under the BPR 8:1 condition, the effect of PCA content was also investigated to control the extent of such behavior. PCA is generally added to suppress cold welding during milling [3]. Fig. 5 presents SEM images of powders milled for 8 and 16 hours under BPR 8:1 and 10:1 conditions with 4 wt% PCA added. Compared to the case with 2 wt% PCA, the 4 wt% condition required up to 16 hours of milling to achieve more than 90% flake formation. This is interpreted as a result of excessive PCA acting as a lubricant between the balls and the powder, thereby lowering the energy transfer efficiency [14].

- Fig. 6 shows the particle size distribution results under the 4 wt% PCA condition, where both BPR 8:1 and 10:1 exhibited a distinct bimodal distribution. This suggests that, at high PCA content, the influence of BPR on particle size distribution becomes negligible, unlike the 2 wt% condition, where clear differences were observed. This phenomenon results from the simultaneous formation of flakes and excessive cold welding. The addition of a high amount of PCA reduced the energy transfer efficiency between the balls and powder, leading to cold welding, while prolonged milling of already flake-shaped powders caused further aggregation due to increased surface energy, a typical feature of flake morphology. As a result, the particle size increased significantly [15]. This observation is consistent with the energy model results, which show that cold welding dominates over fragmentation when the transferred energy does not exceed a certain threshold. This implies that with 4 wt% PCA, the optimal energy is considerably shifted to a higher and broader range compared to the 2 wt% condition, making it less suitable for control morphological transformation. Future work will focus on quantitatively integrating PCA effects into the energy model.

- In summary, the morphological transformation of spherical cobalt powders through high-energy ball milling was successfully achieved. This transformation was strongly influenced by BPR, milling time, and PCA content. Moderate energy input facilitated efficient flake formation, while excessive energy caused fragmentation and high PCA content led to delayed flake formation with dominant cold welding. These results demonstrate the importance of optimizing milling conditions to achieve the desired particle shape.

3. Results and Discussion

- In this study, flake-shaped transformation of spherical cobalt powders was induced via high-energy ball milling, and the effects of key process parameters such as BPR, milling time, and PCA content on the powder morphology and particle size distribution were analyzed.

- Notably, under the BPR 8:1 condition with 2 wt% PCA, more than 90% of the powders were successfully transformed into flake form after 8 hours of milling, confirming this as the optimal condition for flake formation. However, as milling time increased further, cold welding became the dominant mechanism. In contrast, under the BPR 10:1 condition, fragmentation dominated due to higher energy transfer. This behavior was attributed to the difference in energy imparted to the powders depending on the BPR, and the optimal energy range for flake formation of spherical cobalt powders was estimated using the Burgio-Rojac model.

- When 4 wt% PCA was added, flake formation exceeding 90% occurred after 16 hours of milling under both BPR conditions. The resulting particle size distributions exhibited bimodal characteristics, suggesting the occurrence of excessive cold welding. This was interpreted as a consequence of the excessive amount of PCA acting as a lubricant between the balls and the powders, reducing energy transfer efficiency, thereby delaying flake formation and promoting cold welding.

- Through adjustment of the milling parameters—BPR, time, and PCA content—this study successfully demonstrated the morphological transformation of spherical cobalt powders into flake form. The results serve as a foundational approach for shape-controlled fabrication of Co-based current collectors. In future work, these optimized conditions will be applied to Co-Ni alloy powders to fabricate flake-based current collectors, ultimately targeting integration into rSOC systems. Although XRD data were not included in this study, previous reports [16] indicate that cobalt powders can undergo phase transition between fcc and hcp structures depending on the milling intensity under high-energy milling. Based on this, similar structural evolution may also be expected under our milling conditions, which will be further verified in future work.

4. Conclusion

-

Funding

This work is supported by the Ministry of Trade, Industry & Energy (MOTIE) of the Republic of Korea (no.P0028836).

-

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

-

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.

-

Author Information and Contribution

Poong-Yeon Kim: Researcher; conceptualization, writing–original draft

Min-Jeong Lee: Ph.D. candidate; supervision, writing–review & editing

Hyeon Ju Kim: Researcher; investigation (experimental assistance)

Su-Jin Yun: Researcher; investigation (experimental assistance)

Si Young Chang: Professor; writing–review & editing

Jung-Yeul Yun: Ph.D.; corresponding author, funding acquisition, supervision, writing-Review & editing

-

Acknowledgments

None.

Article information

- 1. T. Ogawa, M. Takeuchi and Y. Kajikawa: Sustainability, 10 (2018) 478.Article

- 2. S. Mekhilef, R. Saidur and A. Safari: Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev., 16 (2012) 981.Article

- 3. Naef A.A. Qasem and Gubran A.Q. Abdulrahman: International Journal of Energy Research, 2024 (2024) 36.Article

- 4. H.-S. Joo, J.-Y. Yun and H.-S. Choi: J. Korean Powder Metall Inst., 18 (2011) 1.Article

- 5. S. P. Jiang: Asia-Pac. J. Chem. Eng., 11 (2016) 386.ArticlePDF

- 6. J. H. Zhu and H. Ghezel-Ayagh: Int. J. Hydrogen Energy, 42 (2017) 24278.Article

- 7. S. P. Jiang, J. G. Love and L. Apateanu: Solid State Ionics, 160 (2003) 15.Article

- 8. D. van Impelen, D. Perius, L. González-García and T. Kraus: RSC Sustainability, 3 (2025) 1800.Article

- 9. I. Lee, M. Y. Park, H.-J. Kim, J.-H. Lee, J.-Y. Park, J. Hong, K.-I Kim, M. Park, J.-Y. Yun and K. J. Yoon: ACS Appl Mater Interfaces, 9 (2017) 39407.Article

- 10. Pohang Institute of Industrial Science and Technology and Allantum Co.: Korea, KR 10-2015-0076408 (2015).

- 11. C. Suryanarayana: Prog. Mater. Sci., 46 (2001) 1.Article

- 12. N. Burgio, A. Iasonna, M. Magini, S. Martelli and F. Padella: Il Nuovo Cimento D, 13 (1991) 459.ArticlePDF

- 13. N. Chawake, R. S. Varanasi, B. Jaswanth, L. Pinto, S. Kashyap, N.T.B.N. Koundinya, A. K. Srivastav, A. Jain, M. Sundararaman and R. S. Kottada: Mater. Character., 120 (2016) 90.Article

- 14. D. H. Lee, S. Han, M.-H. Park, J.-Y. Yun, M. Ji and Y.-I. Lee: J Powder Mater., 66 (2023) 679.ArticlePDF

- 15. C. Machio and H. K. Chikwanda: J. South Afr. Inst. Min. Metall., 111 (2011) 149.

- 16. J. Y. Huang, Y. K. Wu and H. Q. Ye: Appl. Phys. Lett., 66 (1995) 308.ArticlePDF

References

Figure & Data

References

Citations

Fig. 1.

Fig. 2.

Fig. 3.

Fig. 4.

Fig. 5.

Fig. 6.

Graphical abstract

TOP

KPMI

KPMI

ePub Link

ePub Link Cite this Article

Cite this Article